Most good business writing adheres to the principles of plain English. And most shocking business writing blatantly disregards them. But what is plain English? Put simply, it’s the difference between this:

Taking all aspects of the matter at hand into consideration – and keeping in mind the forthcoming inputs of multitudinous interested parties – it would not be outlandish to suggest that we postpone our deliberations.

And this:

Considering everything – and remembering many stakeholders are yet to contribute their ideas – we should wait before deciding.

Asking for something to be delivered in plain English is another way of saying, ‘in layman’s terms’. Plain English is clear, concise and free of jargon. It’s easy to comprehend, which is why businesses and governments favour it. It’s also simple to translate into other languages. Basically, it’s functional writing – it’s used to convey information that is itself valuable.

“Have something to say and say it as clearly as you can. That is the only secret of style.”

Matthew Arnold, English poet and essayist

Simple? To the point? Sounds straightforward enough. But writing in plain English isn’t always easy. Especially in the world of business, buzzwords and jargon can make our heads spin, until we’re not sure what we’re even talking about anymore.

What, you ask as you smile and nod, does your boss actually mean when they say, “It’ll take a paradigm shift if we’re to develop the bandwidth to parachute in”? In all honesty, you’ll probably never know. But what you can do is use plain English to limit the number of heads you send spinning yourself.

By applying the tried-and-tested rules of plain English to all your writing – from annual reports to newsletters, emails to blog posts – you can improve your communications with clients, customers and colleagues.

So, what is this magic formula? Luckily, the rules of plain English are quite straightforward. Here are our top tips.

Write in short, direct sentences

The point of plain English is comprehension. And the easiest way to make yourself understood is to keep your sentences short and simple. Give yourself a limit of around 25 words per sentence. Research shows that most readers can understand 90 per cent of a piece of writing when its sentences average 14 words. When sentences start averaging 43 words, comprehension drops to a staggering 10 per cent. So, keep it as brief as you can.

“The most valuable of all talents is that of never using two words when one will do.”

Thomas Jefferson, American Founding Father

The next rule is to make sure that each sentence expresses one idea only. Try not to let any dependent clauses claw in and shred your meaning. It’s the difference between, “Brian is a lovely man – although there was that trouble with the law – but he’s just not my type” and “Brian is lovely, but he’s not my type. And of course, there was that trouble with the law.”

Use simple, well-known words

In sad news for gifted wordsmiths, the principles of plain English advise us to steer clear of the flashy words we loved at university – words like “existential”, “binary” and “scintillating”.

Plain English is about communicating information – it’s not about communicating your intelligence. So, why say “demonstrate” when you can say “show”? Why say “objective” when you can say “aim”? And does “in relation to” really sound so much better than “about”?

“Short words are best, and old words, when short, are best of all.”

Winston Churchill, British statesman

Of course, sometimes the more exotic word really is better, perhaps because it conveys more meaning. There is a difference, for instance, between “white” and “ivory”, or between “fix” and “ameliorate”. Just make sure that your motives for picking the longer word are honourable.

Write in the active voice

The mat was sat on by the cat.

What’s wrong with this sentence? Well, it’s simple. It’s written in the passive voice.

This means that the object, or the mat, begins the sentence. We only meet the subject – the cat – at the end. And letting the mat steal the show doesn’t really make sense, because it hasn’t actually done anything. It’s the cat who did the sitting. The mat was just a helpless bystander.

To write in the active voice, you put the subject of the sentence first, then the verb, then the object.

The cat sat on the mat.

Much better. To phrase it simply, if you can finish a sentence with ‘by zombies’ then you’re in strife.

More seriously, though, the passive voice is the enemy of plain English. It creates ambiguity where there should be clarity. “A terrible mistake was made” gives us much less information than “I made a terrible mistake”. We know something occurred, but we have no idea who or what caused it.

Incidentally, that’s why some less reputable politicians and businesspeople favour the passive voice (and why you’ll often see it in legal documents). Unless you’re trying to evade the law like poor Brian, though, keep it active.

Structure your argument

When you’re writing in plain English, the substance of your communication should be the star of the show – not its style. And without fancy language and meandering sentences, a disorganised argument becomes obvious pretty quickly. When you cut the pomp and trim the waffle, there isn’t much left to hide behind. So, it’s crucial that your ideas are clear.

“Good prose is like a windowpane.”

George Orwell, English writer

Before you begin writing, you need to figure out the most logical way to get your point across. This isn’t hard when you’re drafting an email or a press release. But it can be pretty daunting when you’re trying to write a 3,000-word white paper or a seven-minute speech.

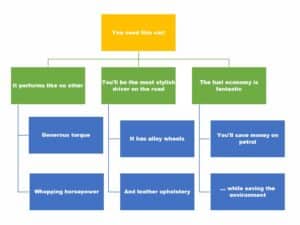

What you need to do is develop a simple structure to slot your ideas and information into. The former McKinsey consultant Barbara Minto suggests building your ideas into a pyramid before you begin writing.

First you consider the apex of your argument. What’s your main point? Next, what’s your supporting evidence? In other words, what pillars are you going to use to prop up this point?

“Clear thinking becomes clear writing.”

William Zinsser, American writer and editor

So, your overarching argument might be that people should buy a certain car. Then, to support this point, you’re going to have to explain the car’s appeal in terms of performance, style and fuel economy. And within each of these topics, you’ll probably have sub‑arguments, like in the figure below.

It’s simple – and it’s powerful. It ensures that your overall structure is logical, and it helps prevent repetition in your writing by deciding where ideas, facts and figures will go before you start.

Edit like you’ve never met it

No-one ever goes out of their way to write sloppy prose. Often, it’s automatic. So, don’t be too hard on yourself when you do find you’re reaching for ‘approximately’ even though ‘about’ would do just fine. It’s hard to break the habits of a lifetime, which is why editing can be the most important step in plain English writing.

“I didn’t have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead.”

Mark Twain, American writer

A good editor is a brutal editor. So, it works best if you can somehow forget that it was you who wrote the piece. It might help to re-read your first draft fresh in the morning or go over it in a different location. The more distance you can put between yourself and the writing, the easier it will be to spot pompous words, overly long sentences and the passive voice.

It’s satisfying, too. Editing is a bit like a makeover. Or woodworking, if you prefer. You’ve already done the hard part: planting the seed, tending the tree and cutting down a log. Now all you need to do is whittle it down into something beautiful.

Need help writing or editing a piece of content? Ask us how we can help.

By Greer Gamble and Grant Butler.

Read more

10 words to avoid in your writing

Embracing diversity: How to use inclusive language in professional communications