Diversity and inclusion are no longer just nice to have, or boxes to tick in an annual report – they’re crucial for success.

According to research from Deloitte, organisations with inclusive cultures are:

- twice as likely to meet or exceed financial targets

- three times as likely to be high-performing

- six times more likely to be innovative and agile

- eight times more likely to achieve better business outcomes.

Yet while the number of executives who rate diversity and inclusion as important issues rose by almost a third between 2014 and 2017, many businesses simply aren’t reaching their diversity and inclusion targets. And they’re coming under increasing scrutiny for it.

Language is one area you can’t overlook when striving for a diverse and inclusive workplace. It’s a legal (and hopefully moral) requirement in Australia to ensure language isn’t discriminatory, but it also makes good business sense. As an example, the wrong words in a job ad can deter strong candidates from applying, affecting talent acquisition. And using non-inclusive language can cause some pretty public embarrassment too.

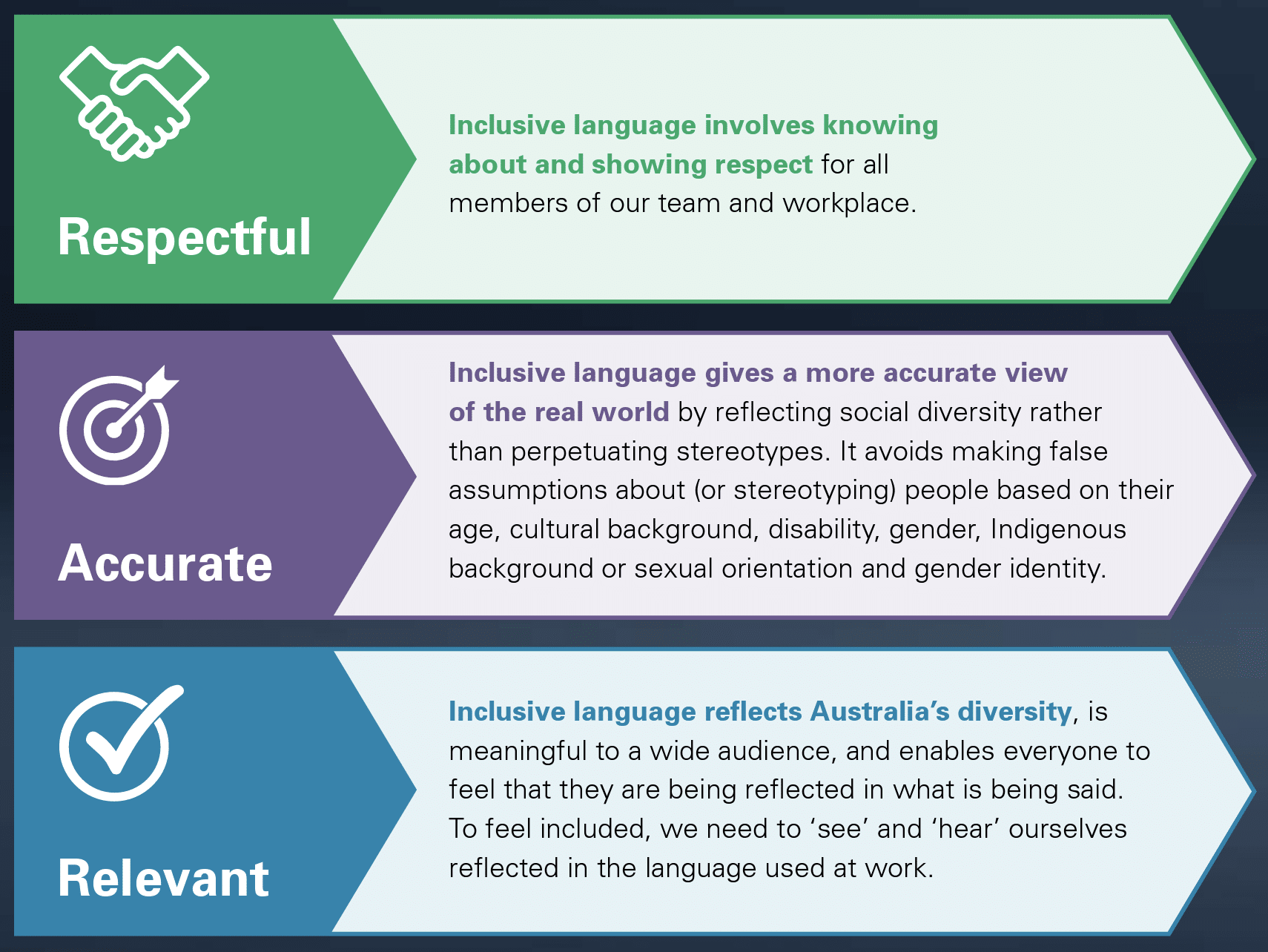

The Diversity Council Australia defines inclusive language as respectful, accurate and relevant. When used effectively, it enables everyone to “feel valued and respected and able to contribute their talents to drive organisational performance”.

From Diversity Council Australia’s report, Words At Work: Building inclusion through the power of language.

Using language to create an inclusive workplace demonstrates that your organisation respects and values all individuals, regardless of age, culture, gender, sexuality or other aspects.

So, here are some tips for Australian readers.

Talking about race and culture

Journalist Stan Grant said that “Language tells us not just who we are but where we are”. Australia is a culturally and linguistically diverse place, and inclusive language reflects this. By adopting it, you show people within and outside your organisation that it is a diverse and welcoming place to work.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Reconciliation Australia advises consulting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders regarding terminology you plan to include in your communications. However, it does offer some useful guidance for generic references – guidance that also appears in the Australian Government’s Style manual.

Terminology

It’s best practice to use ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’, which reflects the diversity of and within these two separate groups. ‘First Peoples’ and ‘First Nations’ are also acceptable terms. Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals may prefer to be identified more specifically by clan, nation or language group. If you’re not sure if this is preferred or appropriate, just ask the person or people you’re referring to.

As a general rule, use ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘Torres Strait Islander’ as an adjective – such as ‘Torres Strait Islander community’ or ‘Aboriginal peoples’. Don’t use ‘Aborigine’ or ‘Aborigines’, as this directly reflects terminology used during the eras of colonisation and assimilation.

While ‘Indigenous’ also tends to be used for generic references, it is not always preferred. This is because using ‘Indigenous’ to collectively describe Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples diminishes the diversity within these communities. Check if it’s appropriate in your communications, and avoid it if you’re not sure. If you do use ‘Indigenous’ when referring to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, always capitalise the initial.

Abbreviations and acronyms

Don’t abbreviate or shorten ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’, unless its acronym (ATSI) forms part of an actual organisation name, such as the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). Also avoid shortening ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ to the pronoun ‘they’, which creates a divisive ‘us versus them’ dichotomy. As the Cultural Capability Enablers Network’s Respectful Language Guide says: “The use of pronouns objectifies Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and creates a social distance between the writer and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, cultures, societies and histories.”

Recognition

Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples at events and meetings and in speeches acknowledges the unique place of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, and as Reconciliation Australia says, shows respect for Traditional Owners.

Two ways to convey this respect are by conducting an Acknowledgement of Country, which both non–Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as well as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can give, and a Welcome to Country, which a Traditional Owner, custodian or Elder delivers. You can also include an Acknowledgement of Country in print and online publications. Common Ground has guidelines for how to include them in your organisation’s communications.

Culturally and linguistically diverse groups

Almost half of the Australian population was born overseas or has at least one parent born overseas. So it makes sense for your communications to reflect and promote cross-cultural awareness, or you may risk alienating your audience and employees. Using plain English – non-technical words and clear, short sentences – can help ensure the widest audience understands your communications.

Names

One particularly relevant area for businesses is how to refer to people’s names. Naming systems vary across the world, and as business becomes more global, it is increasingly important to avoid seeming disrespectful at worst, and careless at best. In some Asian cultures, for instance, the family name comes first. Russian names can have three parts. Portuguese people may have two or more family names.

If you are unsure of how to correctly refer to someone’s name, ask them or do a bit of research (like looking up their LinkedIn profile) to see how they refer to themselves. If you are creating a form for recruitment purposes, use the terms ‘given name’ and ‘family name’, rather than ‘Christian name’, ‘first name’ or ‘surname’, which presumes a certain order and cultural identity that may not be accurate. And make sure you leave adequate space for longer entries.

Australian identities

Terms such as ‘ethnic Australians’ and ‘immigrants’ or ‘migrants’ can erase people’s Australian identity, and creates a false hierarchy of ‘Australian-ness’. ‘Australian’ is an inclusive and accurate adjective for people who were born in Australia or have become citizens. The Style manual advises referring to immigrant groups, if necessary, by “their (previous) nationality or region of origin – ‘Americans’, ‘Spanish’, ‘Vietnamese’…”. Make sure you capitalise these words. Unless it’s relevant, introducing someone by their cultural or racial identity, such as ‘Japanese-Australian Joe Smith’, is unnecessary and can isolate the person introduced.

Language

When it comes to speaking about people whose first language isn’t English, use the acronym LOTE (language other than English) rather than NESB (non-English speaking background). NESB unnecessarily divides people into either English speaking or non-English speaking, applying negative connotations to the latter.

Talking about gender

Avoid gender-specific pronouns (his, her). It’s usually easy to replace these with ‘you’ or ‘their’, or rewrite the sentence to avoid the need for a pronoun entirely. The Style manual lists myriad ways you can avoid gendered pronouns (as does the UN). For example, “Every candidate must provide copies of the application to his referees” can become:

- Candidates must provide copies of the application to their referees.

- Copies of the application must be provided to referees.

- You must provide copies of the application to your referees.

Respect people’s choice of pronoun. ACON points out that “the health and wellbeing outcomes of people with trans and gender diverse experience are directly related to transphobic stigma, prejudice, discrimination and abuse, including when incorrect language is used, often unknowingly”.

If you need to identify someone’s gender, such as on a form, consider providing an option other than ‘male’ or ‘female’– but do make sure it’s necessary to ask.

The easiest way to avoid misgendering people is to follow the prior advice about using gender-neutral language. If it’s relevant, ask what someone’s pronoun is (but don’t ask what their preferred pronoun is – it’s not a preference like tap or sparkling water, it’s who they are).

When it comes to occupations, there’s no need for the outdated ‘-man’ suffix, such as ‘chairman’ and ‘policeman’. Similarly, you don’t need to highlight when it’s a woman’s occupation (‘woman astronaut’, ‘waitress’, ‘female firefighter’ or the shudder-inducing ‘lady doctor’). Make the occupation gender neutral by using ‘person’ – as in ‘chairperson’ or ‘salesperson’ – or refer to the actual job title, such as ‘police officer’ and ‘firefighter’.

Honorifics

Honorifics for women, unlike men, are traditionally determined by marital status and age – ‘Mrs’ for a married woman, ‘Miss’ for a young girl. Writer Ambrose Pierce suggested rectifying the solution by using ‘Mush’ for unmarried men, abbreviated to ‘Mh’ – but it sadly didn’t catch on. So why not, as the Macquarie Dictionary advises, go with ‘Ms’, which doesn’t imply or assign marital status or age, when referring to any woman.

Making assumptions

There are many ways we assume gender in language. Phrases like ‘hey guys and girls’ and ‘ladies and gentlemen’ immediately exclude people who don’t describe themselves in these terms (also note that ‘women’ is the correct noun for referring to adult women; ‘girls’ refers to children). Try replacing phrases like ‘ladies and gentlemen’ with ‘guests’, and ‘guys’ or ‘girls’ with ‘everyone’ or ‘folks’. ‘Parent’ can easily stand in for ‘mum’ and ‘dad’, and ‘sibling’ for ‘brother’ or ‘sister’.

A good (though limited) way to check if your language is biased is to switch the gender in the language you’re using and see what the effect is. For instance, does “John is a feisty CEO” seem odd to you? See this Time article for other ways writers and particularly journalists can strip out unconscious bias.

Talking about sexuality

If it is relevant to discuss sexual orientation, avoid describing it as a ‘sexual preference’ as this implies it is a choice.

Check to see if you’ve made any heteronormative assumptions (assuming that people are exclusively straight). For instance, when referring to people’s relationships, use ‘partner’ or ‘spouse’, rather than ‘husband/wife/boyfriend/girlfriend’. This avoids assuming not only the person’s sexual orientation, but also their partner’s gender.

Avoid expressions that stereotype or treat LGBTIQ+ people as a homogenous group, even if that seems positive. For instance, phrases like ‘gay people are typically more creative’ places inaccurate and unfair expectations on LGBTIQ+ people.

This is only scratching the surface of using inclusive language when speaking to or about LGBTIQ+ and gender-diverse communities. To learn more, refer to this guide from ACON and this one from the Victorian Government.

Talking about disability, impairment or illness

When referring to people with disabilities, put ‘people’ or ‘person’ first. This way, you avoid defining the entire person as just their physical or mental characteristics and instead recognise their whole identity.

For example:

- ‘person with disability’ rather than ‘disabled person’

- use ‘with disability’ rather than ‘with a disability’ as it includes people who may have more than one disability or who don’t attribute one thing in particular to being the disability

- ‘person with a vision impairment’ rather than ‘visually-impaired person’

- ‘person without disability’ rather than ‘normal’ or ‘able-bodied’ person (though make sure it’s relevant to call this out in the first place).

These principles apply for people experiencing mental illness too. Say, ‘person living with depression’ rather than ‘a depressed person’.

When referring to people who are deaf or hard of hearing, the Style manual advises that ‘people with a hearing impairment’ is the most inclusive term, as it can refer to “people with limited hearing to those with none at all”. Though ‘people who are hard of hearing’ is also acceptable, and is used by organisations such as Deaf Children Australia and the International Federation of Hard of Hearing People.

Many people who use Australian Sign Language positively identify as being Deaf (with a capital), similar to how you’d identify as being Dutch, if you were part of that language group.

Euphemisms, parking and declaring

The Australian Network on Disability says to avoid euphemisms like ‘differently abled’, ‘disAbility’ and ‘special needs’, as although they are usually well intentioned, they can come across as patronising.

If you’re describing spaces designed for people with disabilities, use ‘accessible’, not ‘disabled’ – so it’s ‘accessible parking’ not ‘disabled parking’. Keep this in mind for event announcements and invitations.

Does your business ask for a ‘disclosure’ or ‘declaration’ of disability in onboarding forms or other contexts? The Australian Network on Disability advises against using this language as it implies that disability is a secret or somehow shameful. Instead, use something along the lines of ‘choose to share information about disability or impairment’.

Victims and heroes

Don’t describe people with disabilities as unempowered, unhappy or otherwise needing pity – this implies that just because you have a disability, you must be unable to live a rich and fulfilling life. For the same reason, avoid terms like ‘suffers from’ and ‘handicapped’. The phrase ‘confined to a wheelchair’ or ‘wheelchair-bound’ can also imply victimhood (wheelchairs can enable mobility and greater independence). Say ‘uses a wheelchair’ or ‘wheelchair-user’ instead.

Equally, there’s no need to describe a person as ‘inspirational’ or ‘brave’ simply because they have a disability. As Australian writer, comedian and advocate for people with disabilities Stella Young said:

“I want to live in a world where we don’t have such low expectations of disabled people that we are congratulated for getting out of bed and remembering our own names in the morning. I want to live in a world where we value genuine achievement for disabled people…”

A useful language guide

People with Disabilities Australia has compiled this useful language guide. But keep in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all approach and what’s acceptable for one person may not be for another.

Talking about age

When referring to age groups, use inclusive and accurate terms that are appropriate for the context.

The Style manual prescribes that ‘older people’ is generally appropriate, but ‘old’ is a relative term so you should use it with care. Also be careful with ‘senior’ as readers might think you’re referring to a more hierarchical meaning, as in ‘senior executive’, rather than an age group.

If you’re referring to a specific age group, it may be best to simply define it – for example “Older people (defined here as those aged 50 and older) are …”

When talking about young people, the Style manual says the most neutral term is ‘young people’. Avoid ‘youths’, which can have negative connotations.

Of course, official terms such as ‘elder care’, ‘seniors card’ or ‘youth work’ are acceptable.

As ever, using plain English will give you the best chance of both younger and older people understanding you. There’s no need to use older colloquialisms or trending slang in professional communications.

Remember …

The Style manual dictates that “When referring to an individual, that person’s sex, religion, nationality, racial group, age, or physical or mental characteristics should only be mentioned if this information is pertinent to the discussion”. It’s unlawful to discriminate based on these aspects as well as gender identity , intersex status and sexual orientation. So if you plan to mention any such characteristics in your communications, ask yourself if it’s relevant.

Incorporating inclusive language guidelines into your organisation’s style guide can be a great way to ensure everyone’s on the same page. Check out your current corporate style guide and see if could be updated.

If you want to learn more about inclusive language, the Diversity Council Australia has some great resources like this piece on building inclusion through the power of language. But if you’ve had enough learning for today, check out this lighthearted video ‘Words at Work’.