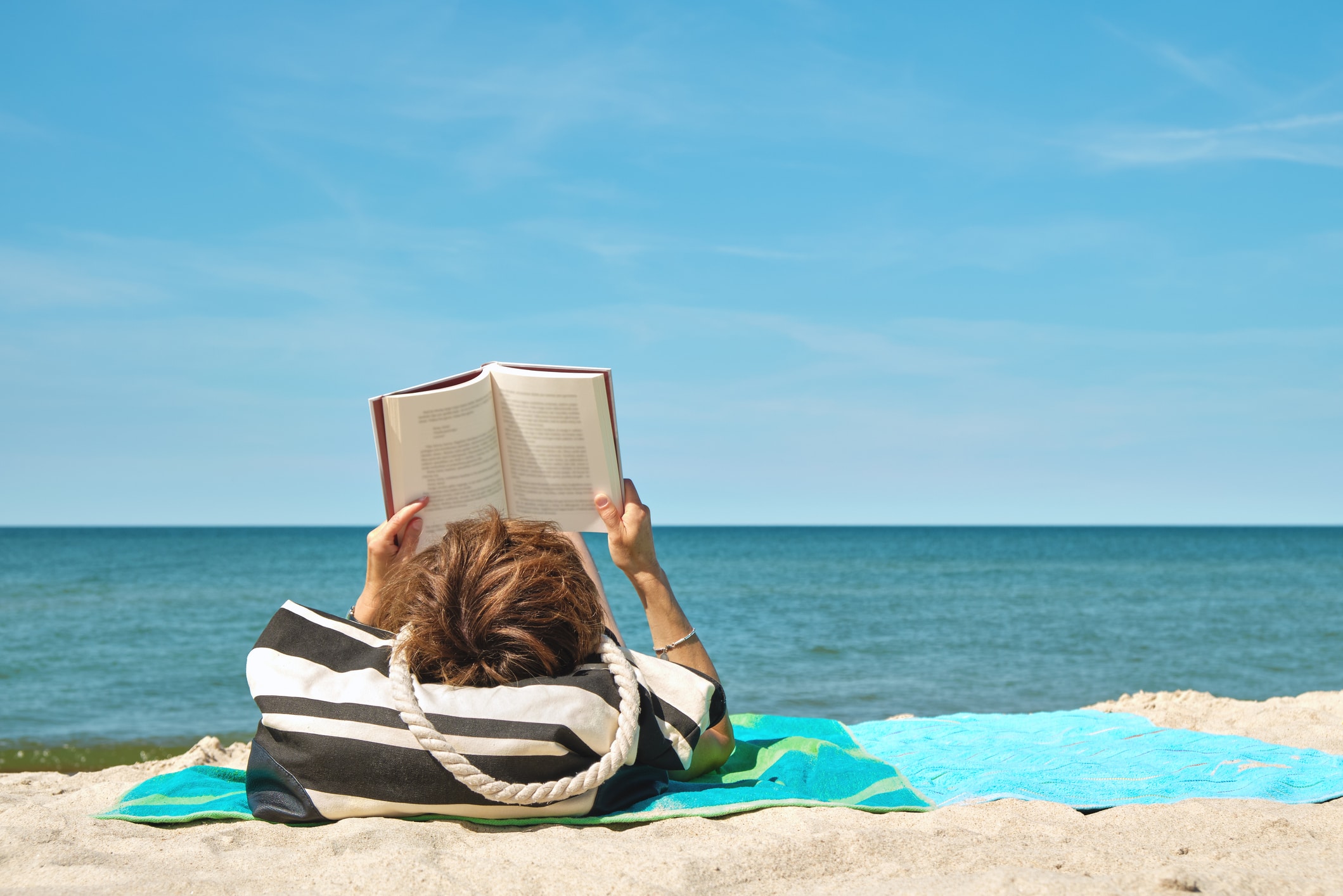

Stone Yard Devotional

Charlotte Wood, Allen & Unwin, 2023

Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional centres on a woman who leaves behind a failing marriage, her friends, and a job she no longer believes in to live with a secluded community of nuns near her old home town in country New South Wales.

Unsettling the calmness are memories of the woman’s mother, who died young. There’s also a mouse plague, the impending arrival of the bones of a murdered nun, and a visit from someone from the past. All serve as catalysts for Wood to explore the nature of goodness, grief and forgiveness – culminating in a reckoning of sorts for the protagonist as she grapples with the questions of her life.

Wood’s prose is beautifully descriptive. She easily conjures up the incongruities of mainstream life and the nuns’ monastic existence – physical and emotional. Stone Yard Devotional is a thought-provoking read.

By Lesley Lopes

Elon Musk

Walter Isaacson, Simon & Schuster, 2023

I’m 534 pages into this 670-page monster and still finding it a lively and enjoyable read, which is testament to both the entertainment and business value Elon Musk provides, and the writing skill of Walter Isaacson.

Isaacson had a high level of access to Musk and draws out some general business lessons that should interest any leader. These include Musk’s huge capacity for work; focus on making processes and companies more efficient; idea of pursuing missions first then building businesses to achieve them; and prioritisation of strategy over things like people’s feelings, which the author and Musk attribute to his Asperger’s. Isaacson’s Elon Musk adds a lot more recent material to the Musk story than you can find in Ashlee Vance’s excellent earlier book, Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, which was published in 2015.

Overall, what I’ve found interesting – and this is not necessarily a criticism – is that the picture of Musk that emerges from Isaacson’s book is very consistent with the one that emerges from Vance’s book, as well as most of the other things that I’ve read about Musk. It seems that what you see is what you get with him, from the brilliant to the mercurial, to the downright odd and offensive.

And given that Musk has often been the first to share many of those moments via X (formerly Twitter) and other channels, it seems there wasn’t a deeper layer or group of facts for Isaacson to discover about him. Which also means one of the wealthiest and increasingly powerful men in the world is incredibly innovative and rational, while also being somewhat puerile, impulsive, foul-mouthed and easily swayed.

So I’d say it’s definitely a good book to hand out at Christmas and an enlightening read, even for someone like me who has already read a lot about Musk. But perhaps consider whether you want to take the hard copy on vacation. Because of all those pages, it is more than two inches thick, so you might want to grab it on an e-reader!

By Grant Butler

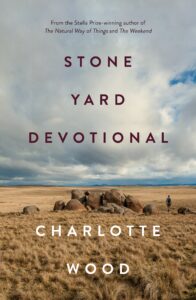

The Bookbinder of Jericho

Pip Williams, Affirm Press, 2023

Not to overuse the phrase ‘much-anticipated follow-up to the New York Times bestseller debut novel’, but if you loved The Dictionary of Lost Words and want to dive back into that world, The Bookbinder of Jericho will be a comforting treat.

Some of the themes are heavy – disability, risk, war and loss among them – but nothing extreme within the realm of popular fiction. Importantly, Williams’s historical fiction does not feel forced – an unfortunately common hazard of the genre.

Recommended companion reading: The Dictionary of Lost Words, of course. And for nonfiction fans, from the author’s own source material: The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary, and The Surgeon of Crowthorne: A Tale of Murder, Madness and the Love of Words, both by Simon Winchester.

By Olivia McDowell

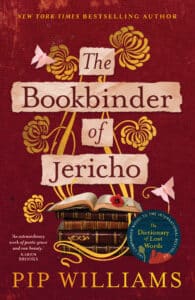

The Conversion

Amanda Lohrey, Text Publishing, 2023

Like Amanda Lohrey’s Miles Franklin winner The Labyrinth, her latest novel is about a woman who uproots her city life to start again in the sticks. She’s dealing with some of life’s big themes – betrayal, death and grief – and the havoc they can wreak on the mind and soul.

Superficially, The Conversion is about trying to renovate a home (a great Australian theme). The deeper theme is about trying to renovate – or resuscitate – one’s mind and soul after an emotional blow.

It’s written in Lohrey’s easy style that beautifully captures every scene, evoking characters and classes through speech and setting. There are moments of brilliance, such as when Zoe ponders how she arrived in her small town set among new vineyards and old mines a couple of hours from Sydney. What remains of the young Zoe? “Only, it seems, her perverse fate, a fine thread in the tangled skein of an unquiet world.”

By Kim Irving

Lola in the Mirror

Trent Dalton, Harper Collins, 2023

A nameless girl on the lam with her mother finds sanctuary in a scrapyard by the edge of the Brisbane River. The two are part of the city’s substantial “houseless” community, and names are risky when you’re on the run.

The one person who might be able to help the girl with no name change her fortunes is the elusive Lola, glimpsed in the shards of a broken mirror.

Like Trent Dalton’s acclaimed debut novel, Boy Swallows Universe, which was based on the author’s troubled childhood in 1980s Brisbane, Lola in the Mirror draws on real life for inspiration. In this instance, the people Dalton met while covering homelessness as a reporter for The Courier Mail newspaper.

With its themes of homelessness, drug and alcohol addiction, trauma, violence and, particularly, domestic violence, Lola in the Mirror should be a bleak read. However, the novel’s underlying love story, redemptive narrative arc and elements of magical realism make it an altogether more uplifting tale.

Dalton has been accused of romanticising homelessness in this novel, which is fair criticism. But it doesn’t take away from the pleasure readers will get from this highly engaging book – his best since Boy Swallows Universe.

By Ylla Watkins

The House of Doors

Tan Twan Eng, Allen & Unwin Cannongate, 2023

Malaysian author Tan Twan Eng has impeccable literary credentials. The House of Doors is his third novel. Like its two predecessors, it was longlisted for the Booker prize. Tan’s second fictional outing, The Garden of Evening Mists, made the 2012 shortlist.

His latest work features two notable historical figures – the popular English novelist W Somerset Maugham (known as ‘Willie’ to his friends) and the Chinese revolutionary statesman, Sun Yat-sen.

A secondary focus is a 1911 scandal involving Lesley’s friend, Ethel Proudlock, on trial for shooting a man dead at her house in Kuala Lumpur. Maugham was later to draw on the incident as the source material for his story, ‘The Letter’, published in his successful collection, The Casuarina Tree. The timing of the Proudlock affair coincides with the visit of Sun Yat-sen to the region, shortly before the overthrow of the Chinese Qing dynasty and Sun’s ascendancy to the presidency of the Republic of China.

The novel can be variously described as historical fiction, a comedy of manners, a character study and a courtroom drama. It’s also an astute exploration of how a writer alchemically transforms the base material of people’s lives into the gold of artistic fiction.

The House of Doors intentionally mannered style – which reflects that of Maugham’s writing – helps Tan to gradually unfold a fascinating tale that addresses colonial exploitation, infidelity, blackmail and closeted sexuality. It also explores interracial tensions, sham marriages, murder and the often-tenuous relationship between perception and reality.

By Peter-John Lewis

On Writing Well

William Zinsser, Harper Perennial, 2006, first published 1976

This might not sound like fun holiday reading, but we’d recommend anyone whose job involves writing take a bit of downtime to consider some of the great books on good writing. Near the top of our list is William Zinsser’s witty and informative On Writing Well, which spans everything from how to construct short, sharp non-fiction sentences to how to overcome writer’s block. Some others are Stephen King’s autobiographical On Writing (2000); George Orwell’s inspiring Why I write (1946) and Politics and the English Language (1946); and the surprisingly lively Plain Language for Lawyers (2010), by Australia’s Michèle Asprey.

As Zinsser says in the introduction to the 2006 edition of his book, when word processors had overtaken typewriters, “Computers have replaced the typewriter, the delete key has replaced the wastepaper basket, and various other keys insert, move and rearrange whole chunks of text. But nothing has replaced the writer. He or she is still stuck with the same old job of saying something that other people will want to read”.

Finally, because the more you learn about great writing, the more enjoyable it is to read anything that’s well-written. And each of these books is simply a pleasure to read – even the dry-sounding one about legal writing.

By Grant Butler

The Black and White House

Karen van Ditzhuijzen, Monsoon Books, 2023

Singapore isn’t only made up of high-rise buildings of glass and steel. In this gripping novel about female friendship and resilience, the island’s grand colonial-era bungalows – colloquially as ‘black-and-whites’ – take centre stage.

When Salimah, a single mother to a rebellious teenager, loses her job, she’s drawn back to the old house in Adam Park where her father once worked as a servant. For her, it’s a place with a dark history – where her childhood was uprooted. By chance, she bumps into Anna, and their lives start to intertwine in unexpected ways.

Having lived in Singapore for over a decade, I’ve always wondered about the history behind some of its older houses. In The Black and White House, Dutch expat Karien van Ditzhuijzen tells a wonderfully atmospheric gothic tale set in one such building.

The two women at the heart of the story come alive in all their aspirations, conflicts, and desperation: I didn’t envy some of the decisions they were forced to make. The supernatural elements add to the charm of this light but finely wrought tale, making this an ideal beach read.

By Melissa de Villiers

The House That Joy Built

Holly Ringland, Harper Collins, 2023

Have you lost your creative spark? Maybe a parent or teacher once told you your painting was no good or your story was rubbish, and you gave up. Perhaps you long to write, sing, draw, dance or sculpt but never seem to get started.

Ringland is the bestselling Australian author of The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart – now a series on Amazon Prime starring Sigourney Weaver and Asher Keddie – and The Seven Skins of Esther Wilding. The House That Joy Built is her first non-fiction book. It’s not a self-help book but a call to action for anyone with a desire to create.

In a series of connected essays, Ringland explains how she moved through grief and fear to return to writing. She offers ideas for combating self-doubt, procrastination, creative block, inner criticism and lack of time.

The House That Joy Built will inspire you to plan your next creative project and get on with it. Have your highlighter and post-it notes ready, as 2024 could be your year.

By Susan Moore

Not Now, Not Ever

Julia Gillard, Penguin, 2022

Julia Gillard’s book, Not Now, Not Ever, marks 10 years since she delivered her famous misogyny speech in parliament as prime minister. Subjected to negative comments in the media about her private life and appearance, she had until that speech largely remained silent. It marked a turning point and resonated with many in calling out bad behaviour and sexism towards women. The book reflects on what the speech meant at the time and what cultural changes have taken place since.

Not Now, Not Ever is an interesting read for feminists, Gillard fans and anyone interested in the government of that time. Her speech certainly created a shift in politics and asked questions about the representation and discrimination of female figures in the media. Hopefully we have forever moved away from a dark place that we won’t be visiting again.

By Jenny Welsh

Trust – A fractured fable

Jeanne Ryckmans, Upswell Publishing, 2023

A ‘distinguished professor of ethics’ who previously had an ‘illustrious career as an investigative television journalist’ cons a prestigious Australian university into ploughing large sums of money into an exciting and ground-breaking project on trust.

The same man scams a businessman in Dubai, appears as an expert witness for Australia’s corporate regulator and charms an unsuspecting woman – Jeanne Ryckmans – into a damaging trans-continental affair.

An exploration of personal relationships, Ryckmans uses spare, unsentimental prose to describe the dramatic mood changes that turn the professor from eccentric intellectual into something altogether more malevolent. As a study of how charlatans infiltrate contemporary institutions, it’s a convincing portrayal of the modern world’s obsession with saleable ideas and chutzpa over intellectual integrity and substance.

Ryckmans is a wry comic observer. The details she assembles for us in her short observatory snippets are delicious – the Irish Professor has a penchant for Yeats, $200 wagyu beef steaks, first-class flight, Hermes scarves and Paddington Bear.

While the chronology of events at the start of the book is initially a little difficult to follow, it’s still well worth the read.

By Meredith Tucker

Translating Myself and Others

Jhumpa Lahiri, Princeton University Press, 2022

Have you ever noticed that a book translated into English reads with a subtle but unmistakable syncopation, like an echo of its original voice? Maybe the translator – or even an editor – could iron this out. But how far could they deviate from the source before it’s just a rewrite? And how far before we lose sight of the source material altogether?

This little book of nonfiction essays is a treat for language lovers and fans of translated writing.

And who better to give deep insight into the subtle art of translation than someone whose native languages are English and Bengali but who chooses to write in Italian, and to translate Italian texts into English – and vice versa.

There’s a fair amount of discussion around ‘the classics’, and of Latin and Italian languages, but not so much as to leave a casual reader at sea. Translating Myself and Others is less a technical book (it’s not at all) and more a gentle ode to the inherent nuance of language – any language – and those who work with it.

By Olivia McDowell